Prisoners of the Subsidized Capitalism Dilemma

Pt III on Returns vs. Impact – Escaping

This is Part III of a series searching for intellectual honesty when navigating returns vs. impact.

You've met Friedmans and AntiFriedmans. Their heated debate, expressed in economic terms, revolves around the treatment of externalities. While economic terms may be repulsive to those who find economics reductive, they are a helpful language for understanding where we are and where we can go - if we’re willing to dig in and work together.

The crux of the matter lies in how we address externalities, positive and negative effects of businesses which are unaccounted for by our economy. While they may not express it this way, both parties simply want a world where externalities are eliminated. Positive externalities, like the long-term benefit of a good teacher on a cohort of children, should be valued by our society. It should be mission-critical. Negative externalities, like the destruction of our environment, should be minimized. More good, less bad – that’s an easy enough future to agree on.

The rift is how we get there.

Friedmans believe in capitalism’s ability to internalize externalities over time.

As each one gets internalized by the market, it becomes more expensive to create negative impact and more lucrative to create positive impact. Humans today are wealthier, healthier, and more educated than ever before. Friedmans find it undeniable that this is causally related to capitalism. This system is the best tool we have to align incentives and achieve impact in the long term. The best action for society is the most profitable one. This is how we iterate towards where all externalities are internalized and the debate between returns and impact is null and void.

I call this capitalist utopia Perfect Pricing. It is only a theoretical state. An unachievable limit.

So should we abandon this theory? Or is it a worthy pursuit, allowing us to maximize our use of the ultimate incentive and scaling machine - capitalism?

Subsidized Capitalism: The Gap Between Utopia and Reality

We do not have Perfect Pricing.

Natural Capitalism offers a simple litmus test. In 1997, a working group attempted to find the economic value of one giant category of externalities: nature. It is estimated that each year, we receive $33 trillion of ecosystem services from nature - temperature regulation, cleaner water and air, meat, vegetables, rain, sun, shade - all of it. We don’t even have to debate whether this is adequately internalized by our economic system, because it is more than our entire economic system in 1997 (global GDP was $18 trillion). Our $18 trillion economy was subsidized by nearly 2:1. And this is just nature. The true subsidy of our system includes all externalities.

The takeaway is simple - we are not even close to Perfect Pricing. Our reality is Subsidized Capitalism, a state where externalities remain un-internalized.

The cost of these externalities, good and bad, is not captured by the market. Therefore, “market rate”, as we know it in prices and returns, is a “Subsidized Market Rate.”

At this point, Friedmans should be pushing to get from subsidized capitalism to unsubsidized capitalism, a Perfect Pricing Utopia, fervently. That is the promise of capitalism - to devour externalities, internalizing and converting them to riches and birthing our ideal society in the process.

And to be fair - in many cases, they are. Innovation, a pillar of capitalism by design, is constantly eliminating externalities. We have carbon-absorbing rocks that help farmers grow more crops. We have machines that can print houses from dirt, eliminating dirty supply chains. Business and tech innovation are still the frontlines of externality elimination. They are the best way to maximize low-hanging fruit.

Yet countless externalities remain without a path to profit-maximizing internalization technology (say it again, but faster). There are places where the markets can not yet reach. The commons are continually degraded without any cost. Why can’t we escape these externalities?

The Prisoner’s Dilemma of Subsidized Capitalism

It turns out, Friedmans aligned around a theoretical systematic outcome.

In reality, in subsidized capitalism, individual actors are rarely engaged with such high-falootin’ intent. A job put food on the table. A company gives people purpose. An employer provides stability. At the individual level, capitalism is most often used simply to meet needs.

This is not a critique of that either. Hurt people hurt people. No progress is possible when needs aren’t being met.

This also means, at the firm-level, we can rarely afford to internalize externalities. Most often, this means simply bearing more cost. Now we’re jeopardizing the business, which means jeopardizing our needs. And our competition, well they’re not going to internalize those externalities either. If we eat the cost of those externalities, they’ll eat our lunch.

This is the Prisoner’s Dilemma of Subsidized Capitalism. It is the trap of our own human needs, provided for by our job, our employer, our economy, that prevents us from internalizing externalities.

Back to the example of our $33 trillion worth of ecosystem services, there are numerous examples of attempting to internalize these to maximize their health. Carbon markets are the easiest example. We can see the Prisoner’s Dilemma in effect by simply examining the market size of voluntary carbon markets compared to regulated ones. Regulated markets, where the price of emitting is forced upon the market, are worth $851 billion. Voluntary markets, unregulated but driven by the free market incentive machine, are worth just $2 billion.

Friedmans should be championing the idea of internalizing the cost of emitting, eager to buy up carbon credits and expand the voluntary market’s free-market reach and negating the need for regulated markets. We’re $849 billion of from that reality though. Most of us simply can’t afford to jeopardize the needs being met within today’s Subsidized Capitalism.

The Escape Route: Unsubsidized Price Discovery

Knowing that profit incentives thus far are subsidized, the true pursuit of Perfect Pricing utopia requires discovering unsubsidized prices (or returns).

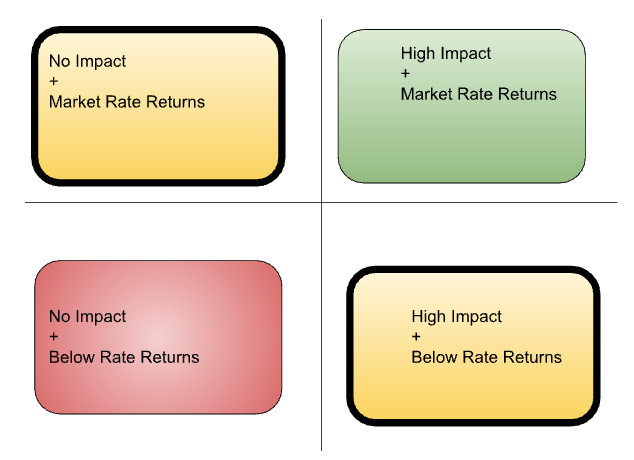

What is unsubsidized price discovery in real terms? It is good old-fashioned problem-solving. It is simply identifying the externality and prioritizing its solution. It is impact first and returns second.

During unsubsidized price discovery, customers should expect higher prices, businesses should expect lower margins, and investors should expect lower returns. At least compared to the subsidized rates.

Let’s return to the ecosystem services example. What does it look like to do price discovery while accounting for nature?

Imagine if traditional land investing had a subsidized market rate of 10% IRR historically. Well, our rainforests are getting bought up and destroyed, and they occupy land. A land investor could invest in the rainforest to prevent clearcutting. What is the rate of return to make that a worthwhile investment?

It may not be 10% to start. But is 9% enough? Or 6%? Or even 0%?

The unsubsidized rate is the monetary return, plus the actual societal benefit. It is the 5% plus healthier rainforests.

Price discovery starts by ensuring the societal outcome is achieved - that the externality is internalized. However, assuming adequate impact is achieved, it then requires profit maximization. It prioritizes internalizing externalities but still aims to unlock the best market rate.

Sometimes, the unsubsidized market rate improves enough to beat the previous rate. This is Patagonia taking lower margins to clean up its supply chain. In the process, they may have unlocked a marketing message that leads to even higher long-term profits. When it does work, the market has then found a viable path out of the Prisoner’s Dilemma. Individual firms are free to pursue the unsubsidized return, as it is also the return that better provides for their needs.

Sometimes, the unsubsidized market rate is still lower than the subsidized rate. The market is still not mature enough to know how to internalize this externality. Good deed goes...rewarded. And this is not for nothing. We already got the good deed - the cleaned-up supply chain. Lock in the impact. Then, keep iterating to unlock the best return.

This may sound like a rebuttal to profit-seeking Friedmans. However, it is a long-term Friedman purist's dream.

When profit and impact can not be simultaneously unlocked, in economic jargon, we are free to focus on un-internalized externalities. It is the economic imperative to problem-solve for the world we want and then help capitalism catch up. Through unsubsidized price discovery, Friedmans and AntiFriedmans can work together to find the escape route from subsidized capitalism and build the future we all want.

In other Innovative Finance News

Insightful > “It is estimated that each year, we receive $33 trillion of ecosystem services from nature - temperature regulation, cleaner water and air, meat, vegetables, rain, sun, shade - all of it. We don’t even have to debate whether this is adequately internalized by our economic system, because it is more than our entire economic system in 1997 (global GDP was $18 trillion). Our $18 trillion economy was subsidized by nearly 2:1.”