High-Growth Potential: The Real Magic Lies Beyond the Funding Source

Challenging the notion that traditional Venture Capital (VC) is required for large equity outcomes and revealing the hidden potential of non-VC-backed firms.

In this article:

Traditional VC can generate significant outcomes, but it’s not always required

Data revealing the untapped potential of non-VC-backed firms

Characteristics of high-potential firms are independent of their funding source

My recent visit to Disney World sparked some reflections on the enchanting allure of VC and its perceived transformative power. Like the captivating world of Disney, VC is portrayed as the magical catalyst for making dreams come true and transforming startups into unicorns.

However, beyond this glittering narrative, there’s a more complex truth. Startup growth isn't a one-way street paved with VC gold. Instead, multiple paths lead to success, and high-potential firms share a common DNA, regardless of funding source.

Traditional VC deal structures obscure the potential of non-VC-backed firms.

Detailed View of a Small Area

The narrative surrounding venture capital (VC) is often skewed due to the limited sample size used in many studies. Most of the data, charts, and headlines we encounter are based on the small subset of companies that have already chosen the VC path.

To put this into perspective, fewer than 5,000 VC first checks are issued each year, compared to the 1.5 million business filings per year, and this only includes those businesses that anticipate having employees.

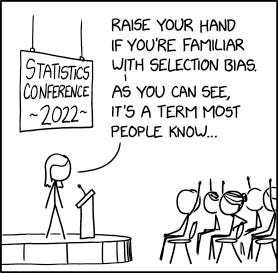

A textbook case of selection bias.

Another example is the commonly quoted statistic that a VC-backed company is 500 times more likely to achieve an IPO or significant acquisition. While this may be mathematically accurate when comparing VC-backed companies to all companies, it's not a fair comparison. It's akin to saying you're 500 times more likely to meet Mickey Mouse at Disney World than anywhere else.

To truly understand the landscape, we must step outside the confines of this 'VC theme park.'

However, finding specific data that compares 'like-for-like' companies - those with equal chances of success but with differing funding sources - is challenging. Most studies are conducted within or outside the VC sphere, making direct comparisons difficult.

So here is the question we should be asking:

How do companies with similar chances of success differ in their growth trajectories based on whether they received venture capital or not?

A beacon of clarity in this fairyland is a study from Dartmouth's Tuck School of Business, aptly titled "Hidden in Plain Sight." This academic research offers a more balanced and realistic view, revealing a landscape where a significant number of firms flourish without the golden touch of venture capital. These firms, often overlooked, share striking similarities with their VC-backed counterparts.

The findings from this study reinforce the notion that the characteristics of high-potential firms are largely independent of their funding source.

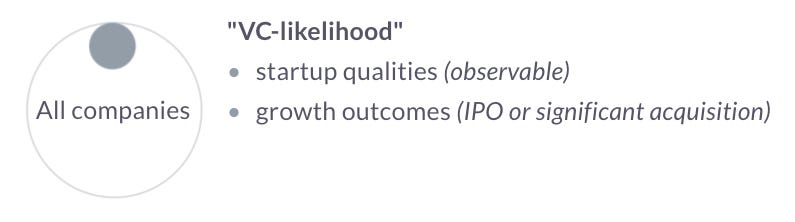

The study defines companies by specific qualities observable at startup (how it is structured, or whether it is registered in DE, etc.). It links them to “equity growth outcomes,” regardless of whether they raised VC or not. This quality is labeled “VC-likelihood.”

They randomly selected a sample of 50% of the companies created across 20 years (over 10 million observations) and sorted them into the “VC Likelihood” category. As a result, the “VC Likelihood” category contained all companies statistically predicted to achieve an IPO or significant acquisition outcome.

This sounds more like it– a map of the world, not just one theme park.

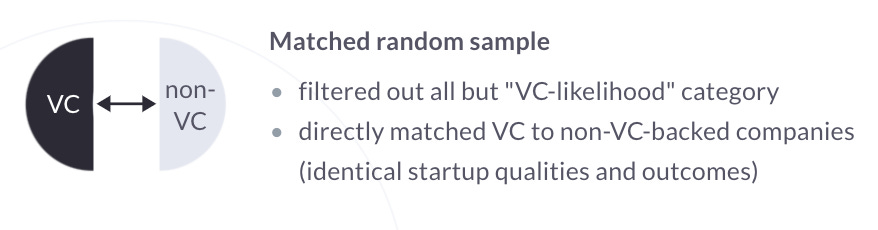

For a direct comparison, VC-backed companies were paired with non-VC-backed ones with identical observable attributes, ensuring a match down to the same zip code and startup date. So, if two e-commerce companies started in Topeka, Kansas, in 2012, each with one founder, structured as an LLC, registered in DE, but only one raised VC funding, they would be paired for comparison.

The result is an A/B test of companies by funding type.

When matching the characteristics of startups that achieve a growth outcome with or without venture capital, the study found:

99% of the difference in outcomes between VC-backed and non-VC-backed firms is accounted for by characteristics that are observable at founding.

So, an interesting paradox emerges.

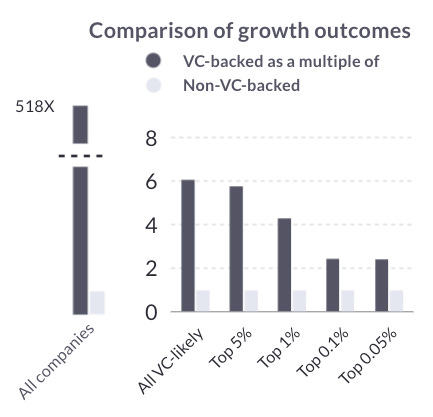

VC-funded firms are six times more likely to achieve a growth outcome than their non-VC-funded counterparts of similar quality. However, the dynamics change when we zoom in on the firms that correlate with the most potential for an equity growth outcome.

Firms in the top 0.1% of the VC-likelihood category are only 2.4 times more likely to grow with VC funding than without it. This suggests the marginal contribution of VC diminishes among high-quality firms.

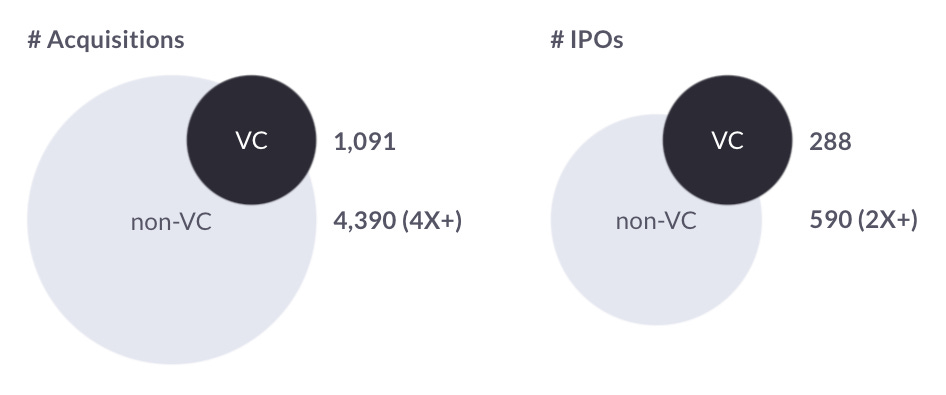

Interestingly, despite the marginally better odds with traditional VC for the top 0.1%, the real eye-opener in this study is that non-VC-backed companies outnumbered the VC-backed companies 2 to 1 for creating unicorns and achieved four times as many significant acquisitions.

They may be undercounting non-VC numbers because non-VC-backed events are more challenging to track than VC-backed events.

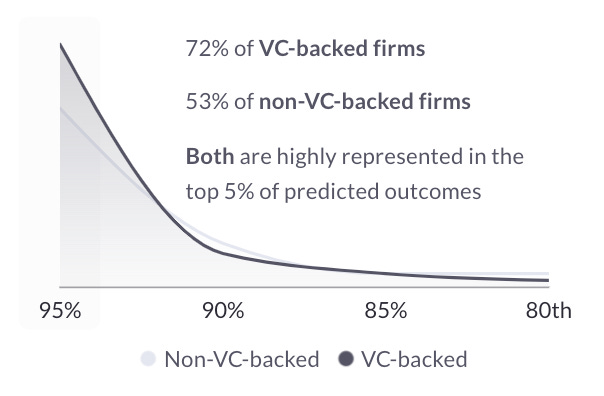

When examining companies categorized in the VC-likelihood group, both VC-backed and non-VC-backed companies tended to be at the upper end of the high potential distribution, where our deeply ingrained narrative says only VC-backed companies should be.

In fact, 72% of VC investments and 53% of non-VC-backed companies rank in the top 5% of the firms most likely to have an equity growth outcome (“VC-likelihood”). So half of the firms that never raise VC are among the top 5% of firms most likely to receive VC.

Interestingly, VCs invest in companies down to the 50% percentile of the VC-likelihood group, illustrating a wide range of investment criteria.

This highlights a clear limitation of access and deal structure “fit” and a significant untapped potential for capital allocators.

Implications for Innovative Finance

These findings challenge the traditional belief that there is only one way to fund the most significant startup outcomes, while other paths simply have lower outcomes. Furthermore, they underscore the potential of non-VC-backed firms, suggesting that alternative funding sources can be just as effective, if not more so, in some instances.

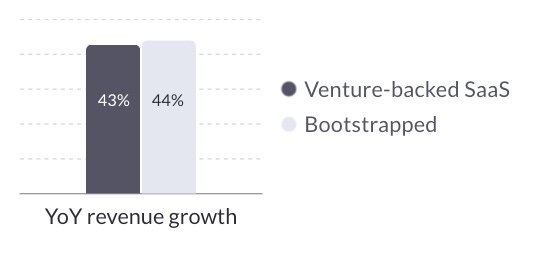

A report from startup lender Capchase echoes this sentiment. It found that SaaS startups with between $1 million and $15 million of ARR saw nearly identical levels of growth over the last year, regardless of whether they raised venture capital.

Venture-backed SaaS startups showed a 42.8% year-over-year growth compared to bootstrapped companies, which saw 44% growth.

The definition of “growth” in this report refers to “revenues” versus a “growth outcome” as defined in the previous study. Just another example of how siloed the available data is and how fragmented the definitions of success are.

As we move forward, we can’t ignore these findings and their implications for the potential of the alternative finance space and the need for a broader definition of success.

VC funding can boost growth, but there are other paths to growth outcomes.

High-potential firms can scale without the golden touch of VC backing.

The data doesn’t support the myth that VC is the only route to startup success.

Non-VC-backed firms can and do flourish, and the characteristics observable at founding often matter more than the funding source.

While traditional VC seems magical, it’s simply one powerful investment tool. We need more investment deal structures to fit more companies with high growth potential. Looking at this data and the large number of growth companies that don’t fit (or don’t want) what is now offered as Venture Capital, I can’t imagine being satisfied with the status quo.

In the past fifteen years, as the cost of starting a tech company dropped, the industry adopted Seed rounds and SAFE notes. That expanded the companies that VC could invest in. Now SAFEs make up a large portion of the first checks, and we rarely see an A round without a Seed round preceding it.

The VC-adjacent market is an even bigger opportunity.

We know ideas come from everywhere, and startups thrive anywhere. So when we see data revealing that the potential of high-growth companies is independent of funding type, we should be radically expanding deal structures and algorithms to match the diversity of high-growth companies (possibly adapting to each company trajectory).

There has to be more research in this area that isn’t limited to just the companies that fit the traditional VC mold. I’d like to see a study that looks at when funding occurred in a company’s lifecycle. Many didn’t use venture funding until well after the startup phase. Shopify (6 years), Braintree (4 years), Ipsy ($150M in revenue pre-VC), Wayfair, Mailchimp, Shutterstock, Atlassian, SimpliSafe, on and on).

Are there more studies that aren’t siloed into one type of funding or look at separate sectors (SaaS, health, fintech, etc.), founder backgrounds, or geography?