From Static Transactions to Dynamic Partnerships

A Case Study

By treating venture capital funding as a dynamic process rather than a static transaction, investors can adapt to changing market conditions and entrepreneur needs. This is a practical example where deal terms were modified after the initial investment, showing that a flexible approach can create win-win situations and reshape the overall performance of the portfolio.

In his book Loonshots, Safi Bahcall’s research showed that business success is found by those who can concurrently maintain a robust core business while embracing innovative, niche opportunities. Capital allocators underutilize this dual-track model. We often view funding as a static transaction more than a dynamic partnership adaptable to changing circumstances.

Venture capital tends to operate in decade-long cycles, reluctant to adjust. Terms like "SAFE," "Unicorn," and "Seed" round are 10-15 years old. We embrace these structures for their efficiency. It makes our work easier.

However, our investment strategies shouldn’t be so rigid. We expect agility from our portfolio companies, demanding their swift adaptation to new information. Shouldn't we, as funders, display the same responsiveness?

We have a core set of funding structures that work (for some). Alongside that, we need to keep testing new tools to fund companies with different finish lines and founders with different starting lines.

While we've created flexible terms for various situations, these initial agreements are limited by an ability to predict the future. Perhaps we can expedite this process, using existing tools but adjusting them in real time as conditions shift?

We can work faster by course-correcting within a single deal structure. We can use the same tools but adapt them to partner with founders as conditions change.

So, we tried it.

Thirty-six months after initially investing, we modified our deal terms with a founder raising a preferred equity round.

Fostering True Partnership: A Case Study

Meet one of our portfolio companies. They are a highly scalable tech-enabled platform, bridging the gap between in-person needs and early-career service providers. Our investment was just before the pandemic disrupted their business model.

Consequently, they were forced to delay their first preferred funding round and prioritize achieving positive cash flow. This meant a longer cycle to a markup and lower IRR and potentially a higher hurdle to a large overall return. The founder was facing a different approach to the balance sheet (more debt? refinancing?), a talent shuffle, and changing service provider terms—a lot of new variables, but relatively easy to define.

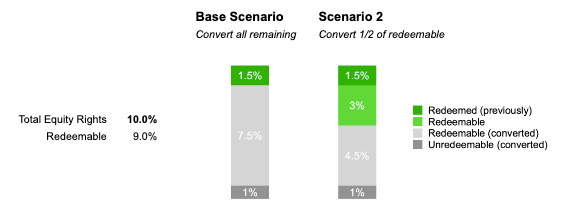

We initially invested $200k for a 10% right to equity whenever they raised a preferred round. 9% of that was redeemable in exchange for 2.5X the investment.

They planned to raise a funding round twelve months after our investment.

That turned into 30 months.

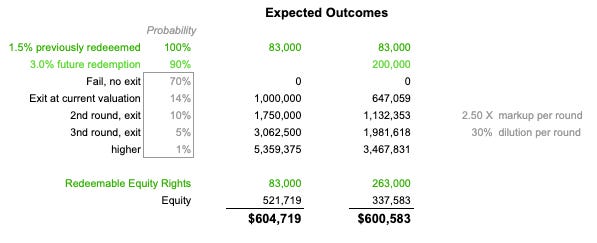

Even under the circumstances, they eventually reached cash flow breakeven and redeemed 1.5% of the equity right for ~$83,000.

Deal Makeover: Balancing Growth, Cash Flow, and Future Potential

They eventually raised the next round (2022) with a pre-money valuation of $12.5M. Converting our unredeemed equity percentage (8.5%) into the new round would result in a 6.25x markup on the remaining 85% of the investment.

But the founder wanted to preserve equity for future growth rounds and was considering reducing the size of the current raise. The founder could preserve equity by redeeming 7.5% but would need to find the cash.

Either path would create a growth speed bump:

smaller raise = slower growth

more debt = less cash flow

Nearly every GP I chatted with wondered why I wouldn’t just convert all of it to bolster our paper markup, which is crucial for our subsequent fundraising presentations. That’s the game we play, round to round, markup to markup. Keep the winners and drop the rest. Raise the next fund.

But converting everything to equity meant doubling down on the “all or nothing” play. This didn’t look optimal when the “all” was less likely and probably smaller than predicted three years earlier. And the “nothing” didn’t apply anymore, either. The company was cash-flowing. We could potentially take something off the table earlier.

Resetting the deal

Here is how I thought about it.

Assumptions:

The potential for a “return the fund” equity play had likely gone down, but decent equity multiples (say 5-8X) were still possible within a reasonable timeline.

There was an increased likelihood of realizing a 2.5X multiple through equity redemption from a growing, cash-flow-positive company.

We could find a realistic balance between converting the remaining equity and retaining future equity rights.

General exit probabilities based on this research (a little dated) indicate less than half of companies that secure a first round of venture capital also raise a follow-on round. And 67-70% of all companies that raise a first-round either fail or don’t achieve an exit.

We understood the company's growth trajectory better three years in.

If we treated the transaction static, we would have converted all the remaining unredeemed equity rights into the round (8.5%), minus whatever the founder would have been able to redeem by scraping together other funds.

We explored several other scenarios and ended up with Scenario 2. One-half of the original 9% redeemable amount (4.5%) would remain redeemable, and the other 4.5% would convert in this round. Along with the 1% that wasn’t redeemable, the total conversion percentage was 5.5%.

There are more sophisticated methods to calculate expected outcomes and probably better data. Still, this back-of-a-napkin approach applied reasonable outcome probabilities and valuation while adjusting for markup and dilution to estimate an expected return.

Comparing both scenarios revealed almost equal absolute returns.

Two variables not included in the above add to the argument for Scenario 2:

Same cash on cash, but a higher IRR because of the much higher probability of returning capital earlier.

The potential for any remaining unredeemed equity rights to convert into the next round at a higher markup (the conversion right is a percentage, not based on future valuation).

Scenario 2 also solves mutual (founder/investor) concerns about growth constraints by increasing future equity availability and lowering the need for current debt.

So what?

The founder’s response to this flexible approach was very positive. They appreciated our willingness to reorient the terms to reflect current realities. Since the restructuring, the company has continued to be cash flow positive and is gearing up for its next funding round.

As an investor, we locked in some short-term returns. We increased the potential to convert our percentage rights into an even more significant raise (regardless of the valuation and undiluted by this round).

This approach seems radical. But the implications for general portfolio management could be significant.

Most companies hit unforeseen headwinds and “shudder” a bit after takeoff. Traditional VC models struggle with these hiccups, often redirecting resources away from these "stumbling" ventures. This approach assumes that these ventures won't substantially impact fund performance.

However, if we can dynamically adjust the deal terms, shifting the trajectory rather than abandoning the venture, we effectively prevent a total loss and maintain some upside potential. Transforming a significant part of the portfolio from zero to returns of 1.5-3.0X certainly reshapes the portfolio's upper-bound performance.

By taking this route, we might land more planes than we crash. And in the process, we're cultivating a host of seasoned entrepreneurs to invest in.

VilCap is looking for beta testers for the latest version of their Abaca product, which includes innovative funding structures. Sign up here.

Jamie Finney and Keith Harrington recently spoke on the RBFN Podcast