The Return Variable

Terms That Scale Series

A lot of “innovative” finance relies on the income statement, specifically one line item on it. I call this the Return Variable. It is the number which is used as a proxy for the company’s performance (instead of its valuation), and a portion of it will get shared with investors (the Percentage).

Some choose top-line revenue. Not accounting for any holiday period on payments, as soon as the company has paying customers, payments start to investors. This also preempts any other expenses for the business, ensuring the returns are not manipulated by padded company expenses.

Others use profit (often via net income), the far other end of the income statement. On one hand, this is pure alignment with profitability. Investors only get returns once a sustainable business has been built. On the other hand, all other annual expenses get doled out before profit and therefore investor payments. Profitability can get delayed or avoided for reasons valid and not.

Lastly, there is a group which takes profit, then adds back in founder/exec compensation, and shares from that sum. It aims for profit alignment, but also addresses the most tempting expense, founder comp.

I can see arguments for each of these and don’t anticipate reaching the single prescriptive solution. Each investor has their own reasons for doing these, specific to their focus, thesis, style of partnership, etc etc. For terms that scale, I think the goal is to make selecting one relatively straightforward for any funding situation.

I see two main places where I anticipate return variable thinking to evolve:

Think of the Return Variable as a Preference. The distinction between common and preferred shares is widely understood and standardized in use. The return variable functions much like common vs. preferred, dictating the order of payout on the income statement instead of cap table. Revenue is the “most preferred”, as it derives returns before the company can use any of that revenue for its own expenses. Profits are essentially common stock preference, if not even below, where investors wait in line for returns alongside common shareholders, after all expenses and budgeted salaries. Thinking about these as a parallel to common vs. preferred may expedite their standardization.

Profit sharing gets a lot of crap for how easy it is to manipulate. However, so long as it is paired with long investor-lock-in, what company can sustain manipulating its way out of profit for years on end? A lot has to go wrong in the investor-company relationship for a successful, profitable company to continue to hide profits to avoid investor repayment for the better part of a decade, which is the length of ride most risk capital investors are used to signing up for. Why orient around this level of paranoia? Or am I naive?

Is there opportunity for the return variable to shift based on triggers? This could prevent negative ones, like hiding profits early on, and reward positive ones, like performance milestones.

The most commonly used return variable is gross revenue. I think this makes sense for simplicity and this will continue to be the case. That doesn’t mean it should be blindly adopted in lieu of thinking through the options more critically.

More Perspectives:

Tyler Tringas, Calm Company Fund - investor utilizing (pioneering really) the use of Founder Earnings

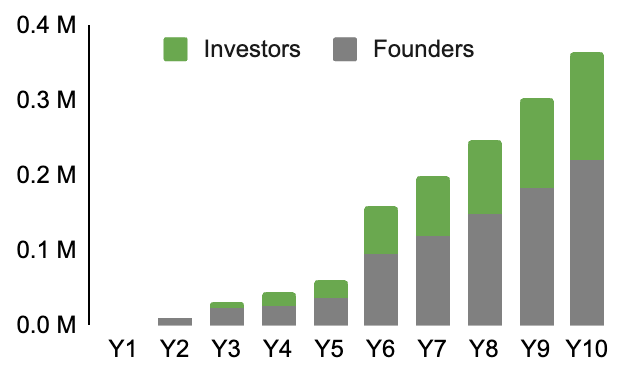

One of our primary goals at Calm Company Fund was to be able to invest confidently in a profit-sharing vehicle while allowing the founder(s) to retain board control. If investors are only entitled to a share of traditionally declared dividends, and the founders have full board control, then investors are exposed to the risk that founders simply increase their compensation to the point where the company is no longer profitable. The heavy-handed way to resolve this for investors to take board control and have the right to approve "fair" founder compensation packages. But this is unnecessary for many businesses.

Founder Earnings directly mitigates this risk by aggregating all the cashflow in the business that could be allocated to the founders—actual founder compensation + net income—and using that as the baseline for calculating the Shared Earnings obligation to investors. This lets founders make their own optimal/tax-advantaged decisions on how to actually allocate those dollars between salary, dividends, or reinvestment, while ensuring that investors are automatically entitled to their fair share.

>>>Learn more about Calm Company Fund and their terms here.

Ines Schiller, Vyld - steward-owned startup founder who raised a profit share based seed round

One of the main reasons for us to go for profit instead of rev. share was that at the point where we had to come up with the terms, we felt we did not have a robust enough model to predict the revenues in relation to the overall company development that we could make sure a rev share would not accidentally blocking us at some point. The second and very basic reason was that we are pre-revenue and as a R&D heavy company we will stay like this for some time. The last point is more a philosophical one but in our interpretation of steward ownership the repayments for investors should only be based on profit as these are the additional worth that is created by the company while fulfilling its mission and therefor can be shared without sacrificing our profit-for-purpose principle.

>>>Learn more about Vyld’s seed round here

What is your take?

Hit Reply so we can incorporate your expertise in future newsletters.

Innovative Finance Jobs