Modeling The Flexible, Place-Based Portfolio

And Building in Floodplains

“The very river that formerly brought life and sustenance to the region now left death and destruction in its wake.” - Rocky Mountain PBS

When the Innovative Finance Playbook first came out, I immediately knew how I wanted to see it put to work. I imagined arming exceptional community leaders with a fund and support network to invest in the companies they are already supporting.

By embracing innovative finance techniques, these funds can be adapted to fit the natural dealflow of any local ecosystem.

By putting local community leaders in charge, we bolster the compensation of a critical, often underpaid role and pre-empt numerous funding biases of the existing, more centralized funding ecosystem.

It sounds good in theory. Does it pass the sniff test?

Let’s find out. But before we get into the spreadsheets…

Welcome to Pueblo, Colorado.

Pueblo lies along the Arkansas River, where the Rocky Mountains collide with the Great Plains. Often, gale-force westerly winds climb up the nearby peaks and jet down the foothills and through town. On other days, storms curl around the southern edge of the Rockies in New Mexico, switching the winds one-hundred-eighty degrees and carrying in wafts of vast farms to the east.

Enduring this violent collision of atmospheric forces is Pueblo’s modus operandi.

In the mid-1800s, it was El Pueblo, a twice-abandoned trading post at the frontier of America’s manifest destiny.

Then came Pueblo’s glory years, when the only “Steel City” west of the Mississippi had over 40 languages spoken locally, newspapers in two dozen languages, and over 20,000 workers at the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company. The most modern hotel in all of the West in 1909 was in Pueblo.

Then came the steel crash of 1982. Today, less than 1,000 people work at the remaining Evraz Steel Mill.

If 1982 was the end of Pueblo’s big business, 2008 did a number on its small businesses too - as with most of America.

All of American history has seemingly left its mark on this frontier rust belt city.

It is the perfect place to test the viability of this local, flexible risk capital fund.

Estimating Dealflow

In 2020, Pueblo had 111,000 citizens and a workforce of 45,300. At a middle-of-the-road 1.5% entrepreneurship rate, that is 679 new local entrepreneurs per year.

Census data indicates that 29% of new businesses are likely to employ others, which rounds to 196 new employers in Pueblo per year and 90-95% of these will need some form of outside funding to do so. That is 176 future employers in Pueblo.

Statistically, 19.3% will use existing financial pathways–banks, government funding, and VC.

This leaves 142 Pueblo businesses in the capital gap. This estimates the number of businesses that are going to employ locals, need outside funding to do so and need to forge their own financial strategy. These are neither the next CF&I nor the next brick-and-mortar Main Street biz. This is the opportunity for the local, flexible Pueblo founder’s fund.

From this 142, let’s take a critical lens as investors and say we’ll only fund 5% of them. This is in the ballpark for funding rates compared to total pitches for a VC firm. While our flexible capital pool lends itself to a far higher percentage of companies than venture capital, sticking with this funding rate ensures our model factors in ample investor discretion.

This gives us seven companies per year to write to local Pueblo businesses. That’s actually a perfect pace for one local community leader to keep up with.

Dealflow checks out.

Modeling The Fund

So how does one write these seven checks?

This is for the locals to decide. Each town will be different. Nonetheless, let’s put a stake in the ground - a blended portfolio of seven businesses in the capital gap per year.

*This is not meant to insist upon the correct portfolio for Pueblo or any particular community for that matter. That will change based on the mix of entrepreneurs and expertise of each community. This is meant to simply demonstrate the mechanics of an innovative local fund with a flexible capital stack at its disposal.

Portfolio Breakdown

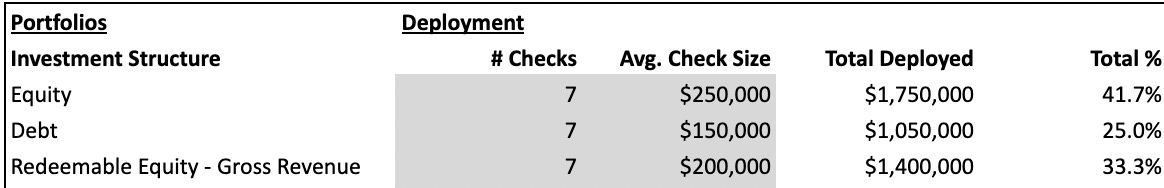

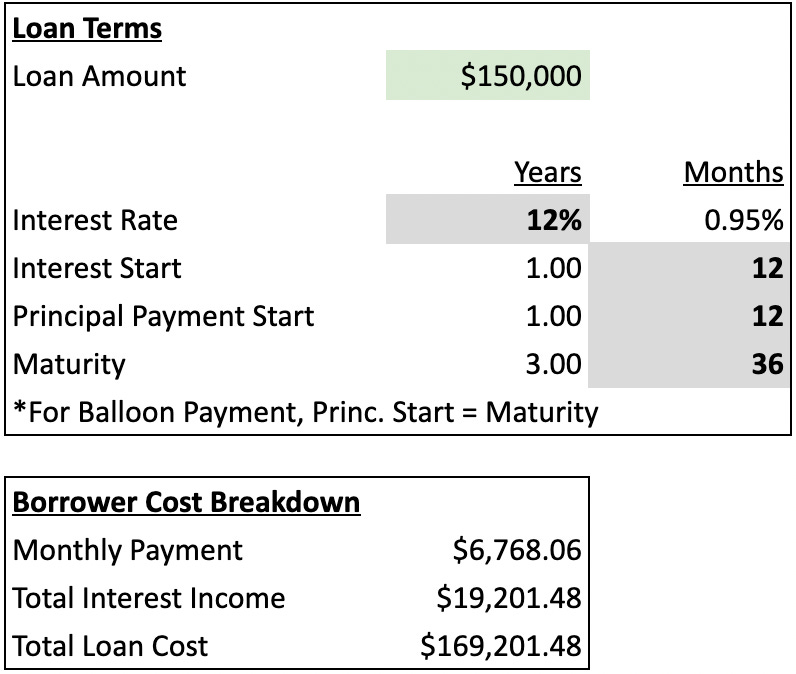

I gave this portfolio a three-year deployment period, meaning we have 21 total checks to write (7/yr). I’ve modeled three different types of investment structures, each making up its own sub-portfolio of seven investments.

Each sub-portfolio is based on a purely theoretical use-case of that investment structure at that check size. Each use-case is meant to demonstrate how a company may end up in the capital gap, unable to access or misaligned traditional debt or VC. These are loosely based on scenarios we’ve seen here in Colorado.

All three target company profiles have an already working business model, as the capital gap is most acute when funding options come up short for an already working business model.

There are endless ways that this will vary in practice, but hopefully, this gives enough specifics to begin to feel actionable.

Let’s dive in:

Equity

In a community without a robust angel investor and venture capital ecosystem (the vast majority of communities), $250k checks are huge. The goal here is to supercharge the first outside investment of local companies.

Rather than model specific deal terms, I’ve opted to model the overall portfolio hit rates. Compared to traditional venture capital, this equity portfolio has a lower loss rate and much smaller exits. This is more representative of the goals and outcomes of normal people outside of the Silicon Valley sphere. The bread and butter of this portfolio are $5-20M exits. These are life-changing for the founder, impactful for the local community, and still too small for traditional VC to get excited. That said, hopefully at least one of these investments can go on to generate a “home run”, which I’ve modeled rather conservatively at a 7x. In this scenario, our fund likely serves as an onramp to the more traditional venture exit path.

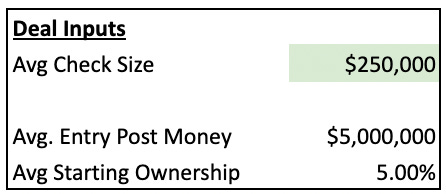

Debt

The debt portfolio is built around a common gap we see where growing, young product companies who need to make their first substantial inventory buy. E-commerce companies are one of the most common business models in the capital gap today. They lack operating history and assets but absolutely need outside funding for inventory the same as a downtown retailer would. Moreover, raising equity is a very expensive way to pay for inventory and often requires them to aim for distant, enormous exits that are too risky and distant to consider at this stage. We’ve seen private debt step in here, simply taking the risk before banks will. It is expensive debt meant to provide a one-time purchase so the company may grow to access cheaper, larger institutional capital going forward.

*The 12% interest rate modeled is market-rate for these types of loans in Colorado, but above usury limits in many other states. However, in my experience, companies at this stage end up with expensive capital, it just shows up in equity or legalese workarounds The fact is, this is still a risky stage to fund, so capital providers require a higher reward (rate) to do so. If your state does not permit loans at these terms, I suggest adapting this model to repackage these loans into debt or redeemable equity.

** Many communities have CDFIs or loan pools with concessionary capital to help them offer lower rates to fill this capital gap. Whenever available, that is obviously preferable. Not all communities are this fortunate however. As a result, this model is meant to be universally adaptable at free-market rates where these pools of capital are not abailable.

The debt and equity sub-portfolios above are not necessarily innovative. They use well-proven investment structures and simply extended their useful range further into the capital gap for early-stage companies.

Redeemable Equity - Revenue Share

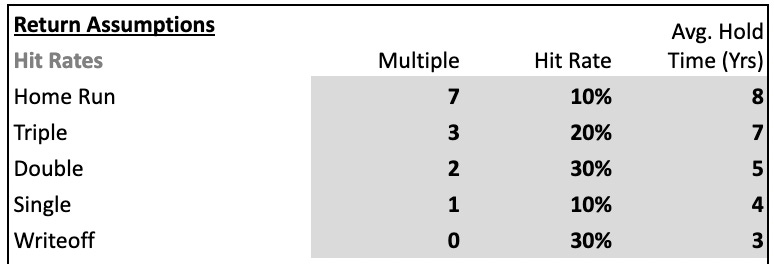

In contrast, the redeemable equity sub-portfolio provides true risk capital at a time when neither equity nor debt is likely to invest. In general, these companies are young and raising for equity-like capital needs, such as marketing or hiring, They’re risky, high-growth ventures, but plan to use profits for future growth as opposed to VC. The default investment scenario is a healthy return via revenue share, with the occasional exit (which I have not modeled in order to be conservative).

*More information on redeemable equity can be found here.

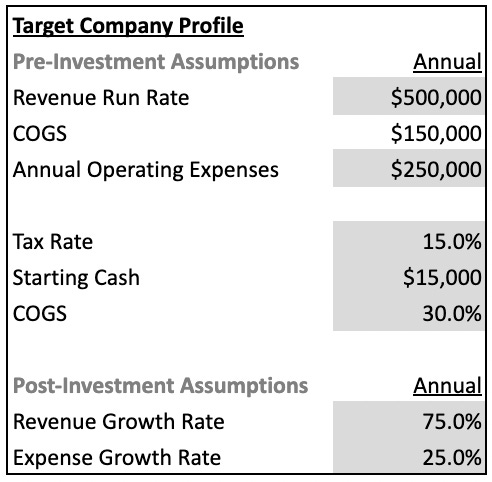

Since returns are a function of real-time company performance, the first step is finding a company profile that would seek this type of investment:

The possibilities to tweak this target company are endless. Is it a software company? Is it a product company? Is the revenue recurring?

For simplicity, it is worth noting a few things that put this company in our target for investment via redeemable equity:

Strong margins - 70%. These have to remain strong or the investment fails.

At or near profitable - the run rate (last month’s revenue x 12) is $500k, but all-in expenses last year were $400k. This means that last year may or may not have been profitable, but at current levels without growth, it will remain in business.

On the precipice of strong, not explosive growth - 75% growth is impressive. It is also not quite on pace to become a fund returner for most venture funds, which usually look for 100-200% growth. The tradeoff should be less failure amongst a cohort of companies compared to VC (which has played out for Indie VC).

Predictable revenue - and even better if it is recurring.

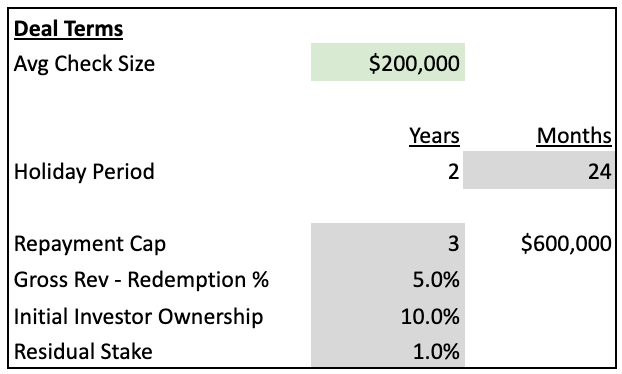

From here, the investment is as follows:

Note that the company is only raising $200k. It has presumably not taken investment yet, or just minimal angel money. Saas and e-commerce are known sweet spots, as both can achieve revenue and scale very capital efficiently. Additional outside funding, such as senior debt for inventory, is also a possibility going forward. Overall, this round is designed for a capital-efficient company to get to cross the $1M mark with momentum in the next couple of years.

*It is worth noting how minimally innovative this portfolio is. There are numerous innovative finance structures that could be incorporated. Redeemable equity is just a starting point. The convertible income share by Chisos Capital, SEAL from Calm Fund, and Tinyseed’s discretionary dividend equity are three that could be adopted to fit local founders too. In fact, there is no reason why they shouldn’t be, their applicability is simply less understood.2

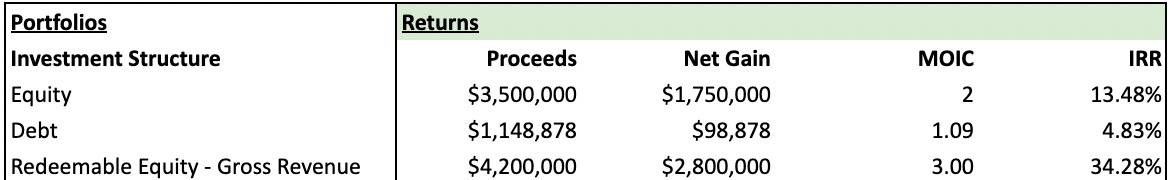

So how does this theoretical local portfolio do?

I’ll keep the numerical performance short. Like any model, the numbers are made up and wrong. They also have the potential to distract from the bigger picture.

(Play with the numbers yourself by making a copy of the model here)

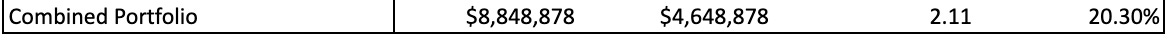

The gross performance of the fund above is a 2.11 multiple on investment and 20.3% IRR. Not bad.

This also ignores:

Any redeemable equity investment that ends up exiting - On paper, this looks like a regular revenue share fund, though it has the ability to reap exit returns too.

Follow-on - We’ve assumed all checks are first and only checks, though there is nothing prohibiting this theoretical local fund from following on should a company require it.

Recycling - Redeemable equity and debt will return cash well before the typical equity fund is used to, though this vehicle is modeled on a vanilla VC fund timeline. This model generates $1.1M in funds during the initial four-year deployment period. These returns could either reduce total investor capital called or be reinvested to leverage invested capital, both of which could increase fund performance by a significant amount if invested to similar success.

The skeptical reader knows that there is a very strong counter-argument to all of the assumptions and claims made above - reality. Investing is hard and outcomes are unpredictable. No arguments here.

Though this misses the bigger point…

The case for small, local, flexible investment vehicles is directionally strong.

This concoction of vanilla-flavored assumptions produced a fund exactly true to the opportunity - somewhere between venture capital and debt. The IRR is that of a strong (but not amazing) VC fund and well beyond a less risky debt vehicle (roughly <15%). 2xish MOIC is right in-line with a median, underwhelming VC fund too. Assuming less risk was taken to reach this 2x, that is a great investment.

It passes the sniff test; it is financially feasible.

To understand the bigger picture, let’s return to Pueblo.

On June 3, 1921, one-third of Pueblo’s downtown businesses were wiped off the map when the Arkansas River breached its banks. Two passenger trains of 200 people were knocked off their tracks, over 600 homes were destroyed, and 1,500 Colorado Rangers were brought in to enforce Martial Law in the aftermath. Official death tolls are debated, but likely well into the thousands when accounting for undocumented families living in redlined low-land neighborhoods. The Great Pueblo Flood was one of the worst natural disasters in Colorado history.

Today, Pueblo is undergoing a self-made renaissance. Ironically, this is most evident where the river ran before its post-flood rerouting. Main Street spans the glassy, winding riverfront walkway and local restaurants dot either side aplenty. Walking around town, one may encounter the neon alley, to-die-for Pueblo-green-chile gelato (seriously), or music ringing out from an underrated bar. The energy is palpable

Pueblo is rebuilding and it knows the danger of building in the floodplains.

Geologically, that is simple.

But where are the economic floodplains?

CF&I was safe, until the flood of the 1982 steel crash. Small businesses was safe, until Wall Street got carried away with mortgage-backed securities. Last week, every startup with Silicon Valley Bank got a glimpse of what it is like to be in the lowlands with the levees about to break.

It is anyone’s guess where the next economic 100-year flood will come from and what businesses will be in the lowlands.

The trick is to foster entrepreneurship wherever it is sprouting, not just where we are used to watering.

This is where new economic pathways come in, and why local, flexible funds are worth trying in every Pueblo around America.

If you like what you read? Forward or repost.

Got an idea? Reply.

Most of all, don’t be a stranger.