Risk capital for individuals is an inevitability, but it ain't easy

Is there a path from worst market possible to major financial unlock?

Will Stringer’s Linkedin profile is a straightforward read. He has held a number of finance roles, each with increasing responsibility.

Come 2020, he struck out on his own to try something big and audacious - a startup.

He needed funding and had a professional network to go to. They likely knew about his work ethic, financial savvy, and maybe even that he had a career overseas as a basketball player.

But his startup? As more conservative finance types, they couldn’t ignore the truth. Startups are a great way to lose money.

My background is more family office, traditional investments, conservative investments - say real estate, private equity - and in the Texas market.

People I went to asked about cash-flow-break-even or income projections. I was living in the startup world and thought, ‘[that's less relevant to these early stage investments. You're investing in hopes, dreams, stories and your belief in this person to execute.’

Will realized that his credibility and long-term career trajectory spoke to his potential, but not necessarily his startup’s potential. They found him backable but weren’t sure his startup was backable.

I witnessed the problem myself.

So I tried to create an instrument that could appeal to those more conservative investors.

This is where it gets meta.

Will’s company is called Chisos Capital. What does Chisos do?

As their site says – “investing in human ventures.”

Chisos invests in individuals like Will, those with high earning potential who are starting companies. It does so using a convertible income share (CISA), the very funding structure Will invented to fund himself to get the company off the ground.

I went to people that I knew and tried to de-risk that investment for them. And so I did the first deal, a convertible income share agreement, for myself.

It's like, ‘Hey, I'm betting on you as a person, Will.

‘I know you and I see your track record of earning income and employment.

‘And if your business doesn't work, I know you'll be fine and you'll pay it back.

‘But we think your business will work, and we'll also get some equity in it.’

So it's kind of a win-win for everybody.

Wait, income shares are not new.

The convertible aspect of Will’s structure is novel, but income shares have a multidecade history. And a checkered one at that.

Education has been touted as the most obvious application of income shares.

In the face of tuition, they’ve been offered as alternatives to student loans. Here’s the overly brief history of income shares in education:

1955: Milton Friedman first proposed the concept of income share agreements in his essay "The Role of Government in Education".

1970s: Yale University attempted a modified form of Friedman's proposal with several cohorts of undergraduate students. In 1999, they canceled all outstanding agreements. The program fatally allowed for early repayment for those who could afford it, but for lower earners, payments stretched out for 30 years.

2002: Lumni Inc. is founded to offer income shares to South American students. Today, Lumni has completed over 21,000 ISAs and has won numerous awards for its social impact. In 2018, it acquired two US-based income-share startups, one focused on ISA for nursing school and the other on Ivy League students. This was meant to kickoff the company’s U.S. expansion, which seemingly has not come to fruition.

2016: Purdue University becomes the first university to proudly and publicly offer student loan alternatives through income share funds, in partnership with Vemo Education. Many other universities set up ISA funds with Vemo, allegedly deploying $23M in ISAs in 2017. In 2021 however, Vemo was sued by 47 students of a coding school it worked with. Student interest in Vemo’s tuition solution also reportedly plummeted and the company has since shut down.

2018: Lambda School, a VC-backed coding school, offers ISAs to its students - 14% of income for four years assuming students land a job paying $50k/yr or more. The coding school would also get sued by a former student, halting ISAs for California students. Now Bloomtech, the company continues to operate, though its tuition options sport a fixed rate financing option and full forgiveness if students don’t find a $50k/yr job.

ISAs simply haven’t found product-market fit for education, at least in the U.S.A. To be fair, the U.S. education market may be the worst place to compete for ISAs.

Most capital markets compete on cost-of-capital they offer, balanced by the risk and reward tradeoff of their returns. 93% of U.S. student debt, or $1.63 trillion of it, is held and guaranteed by the U.S. government and is even harder to discharge in bankruptcy. With subsidized economics, lenders flood the market. With subsidized demand, colleges subsequently hike tuition. And the cycle continues. The result is a capital market that is not accountable to the cost of capital competition but rather maximizes loans made.

Lumni, seemingly the most enduring, impactful education ISA company, remains focused on LatAm where student lending, and lending in general, is far less robust nor as government-backed. So does Lumni work simply because LatAm lending rates are so much more volatile?

Price volatility likely cracks the door open for ISAs to enter the market, but I’d argue this isn’t the main reason for Lumni’s international success.

Cost-of-capital is the wrong game for ISAs to be playing in the first place.

In South America, less than 50% of citizens have a credit score. There is no lender competing for business. Lumni is likely the only path towards affording an education when credit-worthiness is indiscernible. They provided a new, uncompetitive path to education. That is where ISAs should play.

ISAs should provide an unlocking function. They should be risk capital.

As credit and lendability saturate LatAm, the Lumni window will close. A cost-of-capital will be established and pathways to education will proliferate. This may be bad for Lumni, but cheaper predictably priced education is good for people.

So where is there a more secure market for ISAs than higher-ed?

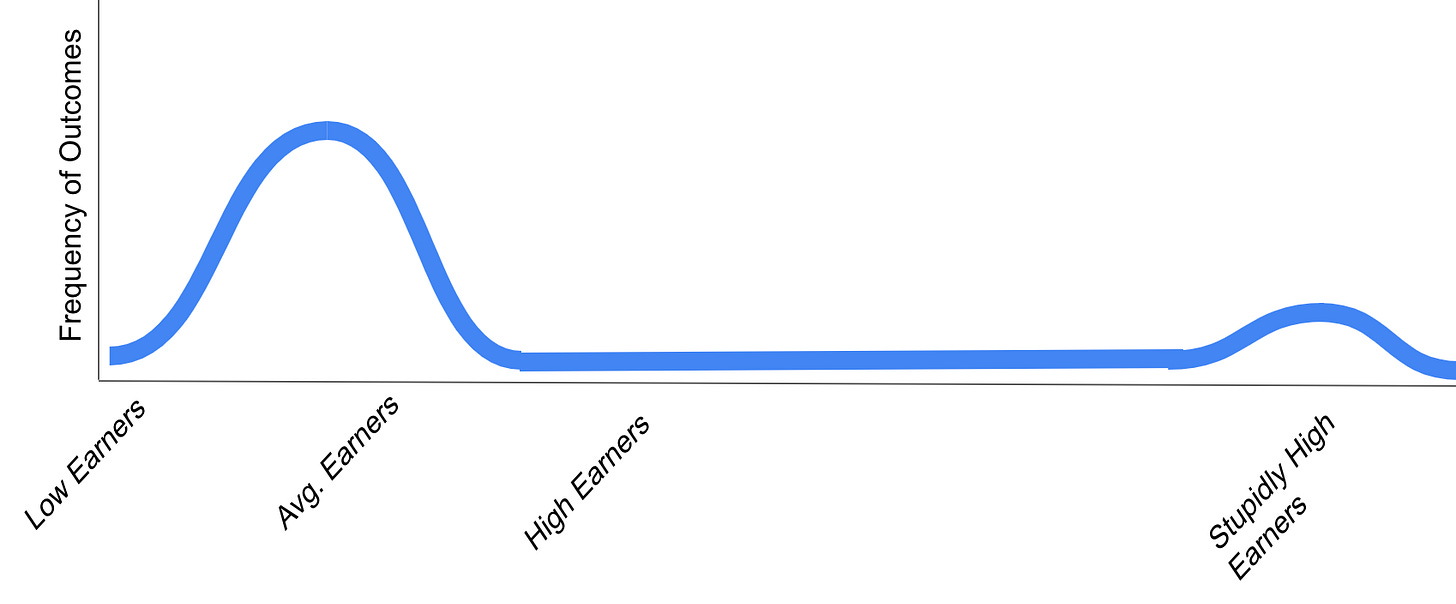

In addition to an unprecedented cost of capital, there should be wide dispersion in outcomes.

ISA portfolio theory has a PR problem.

As risk capital, ISAs are always a better deal for failed investees. The capital may unlock a new path, but that doesn’t guarantee success. For the unsuccessful investees, the cost of capital nears zero. The more failure, the better the deal.

As for the successful investees – they need to be undeniably huge successes. Even if the ISA is a clear unlock, there was zero alternative capital available, investees will compare their outcomes and cost. As a result, the capital cost of mild or medium success, though proportional (say the whole portfolio got the same 10% income share), will look unfair. Life costs and the experience of wealth won’t match perfect proportions. In order to avoid this, ISAs will work best where the successes are too big in absolute numbers to refute the incremental increase in cost of capital.

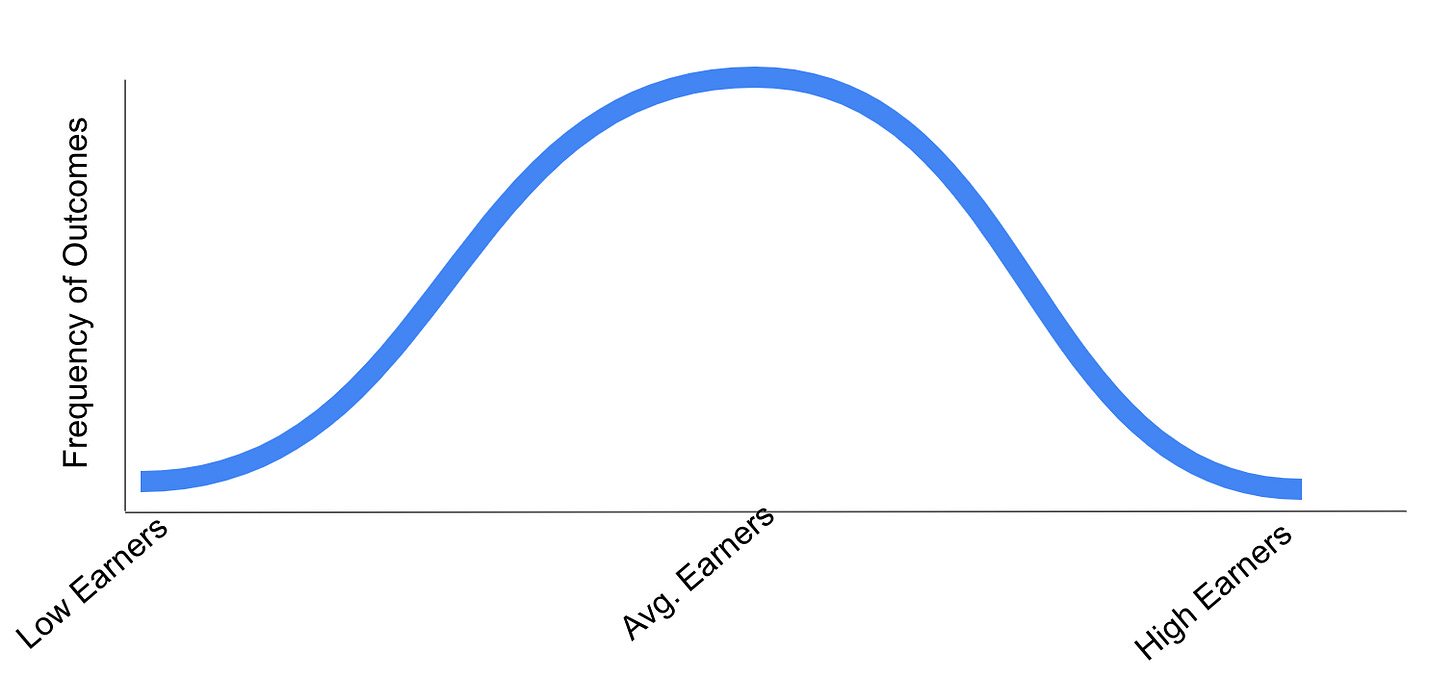

Once again, education is not a great market to prove ISAs. The outcomes are too normal.

ISAs should be proven with portfolio outcomes more like this:

It turns out the sports industry has figured this out. Millions of minor league and amateur athletes scrape by, looking for any edge to break into the far more lucrative professional level. Early risk capital can grease the arduous path from undiscovered in the minor leagues to a big professional contract to an enduring personal brand. Platforms like Big League Advantage and Fantex have spotted the lucrative sports version of this opportunity and invested millions via ISAs, with lots of case studies to show:

While not immune from controversy, the zero-to-hero nature of a pro sports career makes a lot of sense for ISAs. The outcomes are either minimum-wage minor leagues or big-money major leagues.

Sports may be a fringe use-case, but the business of individuals is becoming business as usual.

Widespread risk capital for individuals is an inevitability.

Take Mr. Beast, a household brand… I mean….person. His empire of businesses all started with a social following and likely no LLC. Millions of creators face the same dynamics as athletes, where the winners are miles ahead of the rest of the pack, making them a great fit for ISAs.

Bringing it Full Circle, Mr. Beast has even backed a creator funding provider - Creative Juice. Meanwhile, Slow Ventures (also a Creative Juice backer) has launched their own aptly named Creator Fund, which is “providing creators with ‘seed capital’ in return for a small non-voting minority share of future creative earnings is a win-win for creators and for investors.” Matching the skewed outcome dynamics as athletes, the creator economy is a natural playground for backing individuals and normalizing ISAs.

Meanwhile, “solopreneurs” expand what’s possible by a team of one every day. Previously, individuals incorporated businesses, which could then take on investment, generate revenue, and hire employees. Now, individuals can generate revenue well before incorporating. They incorporate businesses to hire employees and leverage revenue streams, if not only for legal trivialities. As a result, the point at which there is a wide dispersion of outcomes and the cost-of-capital will not reach consensus is day zero. Risk capital for individuals (perhaps even in another form altogether?) is an inevitability.

This brings us back to Will Stringer and Chisos.

While ISAs get fleshed out in relevant verticals like sports and creators, he has been bulding a horizontal foundation for ISAs, or in his case, CISAs.

Will describes the Chisos investee profile as “high-earning potential entrepreneurs.” This includes founders, and Chisos explicitly calls out the sectors they prefer to invest in, via the founders. This places Chisos at the “friends and family” stage in venture lexicon.

And what could be more blatantly biased and in need of disruption than the “friends and family” round? The unspoken truth here is that if you don’t have friends and family who can afford to float your early, unprofitable endeavors, you can’t embark on those types of endeavors.

Uncoincidentally, this harkens back to Will’s own founding story:

As a Silicon Valley outsider myself, I didn't know any angels or VCs, so I went to people that I knew.

“Friends and family” are not only for venture-seeking startups though. Chisos aims to institutionalize this round for all versions of the “F+F round.” The Chisos TAM of “high-earning potential entrepreneurs” preempts all startup criteria, making it theoretically the most inclusive funding out there:

There's a lot of people that have proven some kind of potential, whether that's an earning potential, they've had a good job, they've overcome some kind of large adversity, they've started some kind of early business or nonprofit – just something where they've proven ‘hey, I'm a go-getter; I have great ambition and hustle,’ but they may not know people that can write a 25 or 50 thousand dollar check to help them get off the ground.

From this big tent top-of-funnel, Chisos builds diversity and diversification into its strategy. 80% of its checks are founders planning to raise VC, while some go to founders needing a bridge personally to prove their fundability before the next venture round. They’ve backed numerous saas founders, consumer products, and even one athlete (with many more planned). 30% of Chisos checks are expected to start paying out on day one, while 70% are delayed for 12-24 months. The inputs are intentionally varied.

The resulting portfolio is, naturally, diverse and diversified. Chisos has written checks across 35+ U.S. cities, with 60% to under-represented founders and 40% to founders with impact-oriented businesses. Some founders have gone on to raise VC, converting Chisos in the process. Others have found their startup was right for bootstrapping. Some have closed up shop and continue to pay the CISA upon re-entering the corporate workforce. The outcomes are varied, but at its core, Chisos focuses on unlocking founding potential.

As a portfolio, the horizontal angle can capture unbound upside, assumes modest income, and tolerates losses. Will targets an unlevered (yes, we’re skipping over recycling) portfolio return of 20-25%, inclusive of a 12-15% return on his portfolio of income shares without accounting for equity returns. Altogether, he aims for a 3x on his fund through the resulting exits and ISA payments.

He’s playing where other capital won’t play, providing risk capital, and embracing the wide variety of outcomes.

Does this mean Chiso’s will crack the ISA/CISA market wide open?

Who knows?

ISAs still face major hurdles. The regulatory framework remains fuzzy, having already contributed to the downfall of previous income share providers. Moreover, working with such core human incentives will always keep the door open for critics and fringe cases. It isn’t just a matter of scaling up the funds doing them.

Nonetheless, risk capital for individuals remains an inevitability and income remains the most universal economic incentive.

Who will get there first and where it will take off is anyone’s guess.

Thank you to Will Stringer for helping me wrap my head around ISAs and Chisos. Learn more about Chisos Fund II here.

This piece by Erik Torenburg was also immensely helpful reference.

Any other players (past or present) who would help shape our understanding of income shares?

Innovative Finance (Big) Job Opportunity

The U.S. Department of the Treasury is looking for the next Director of the CDFI Fund