Investing For a Place

Guest-Post by Dustin Mix from "The Small City Segment"

This edition of the Innovative Finance Newsletter features our first guest post. There are far too many brilliant perspectives and opportunities for us not to share.

With that, please meet Dustin Mix.

I connected with Dustin through his newsletter, The Small City Segment. As a rural Colorado focused investor, I was struck by how perceptive Dustin’s newsletter was. By his standard, most of the places I work are not even small cities, yet he was putting words and data to trends which my partners here in Colorado have been circling for years. For me, that’s the tell of good writing.

Dustin lives in South Bend, Indiana, a city of 100,000 with a growing reputation as a rust belt revitalization story. All too often, funds get raised with an interesting thesis, only to go chase the same deals as everyone else. In contrast, Invanti, the fund and studio that Dustin cofounded, exists to actually solve problems for small cities. This ambitious focus yet grounded approach made me fall in love with his newsletter and way of thinking.

My favorite piece of his - Grow or Die is Wrong - is the perfect example of this. While I had sneaking suspicions of growth prerogatives, Dustin crunched the numbers to find an important insight - growth is not synonymous with community health. Not only does he reject a common economic development norm, but he dives into what communities should be focusing on, quality of life and entrepreneurship.

This leads us to today’s post by Dustin:

Investing For a Place

Immediately after I finished graduate school, I moved to Léogâne, Haiti, a city of about 60,000 people 25km to the west of the capital, Port-au-Prince. I had spent three years in two master degree programs exploring new residential housing models in the wake of the 2010 earthquake. My faculty advisors and I had a design we felt might work, so off I went to see if we could implement it with local labor, materials, and partners.

After being there for a few weeks, I met Paul. Paul and his brother were generational residents of Léogâne and had built a small collection of companies and on-going concerns, including a construction firm. He had spent most of his childhood and college in the US, so while my Kreyol language skills were still developing, he made getting things done much easier.

I pitched Paul on our design and construction process and he was immediately in. We learned a lot from each other over the coming two years and built some homes that are still standing today.

Paul was all-in on Haiti and all-in on Léogâne. He didn’t say yes to our project because I painted an irresistible opportunity. He said yes because, three years after the earthquake, he was scouting the world for new ideas that could make him more comfortable, as a builder, that his homes could stand up to earthquakes and hurricanes. But he was also a businessman, so it couldn’t just be interesting. It required the potential to become a sustainable enterprise.

It took me a while to understand the sprawling nature of Paul and his brother’s investments. A construction business, small hotel, gravel business, gas station, cherry farm, motorcycle imports - the list goes on. This is nothing to say of how they invested outside of their businesses - supporting the local Rara festival, building clean water wells - this list goes on. And they weren’t alone. I attended a few local rotary meetings and everyone in attendance was doing the same thing.

I learned a lot from Paul and his brother while I lived in Haiti. A decade later, I’m still learning from them. And after 10 months of exploring small cities, one of their most profound lessons has come to the surface.

Investing For a Place, not just From a Place

I have a simple definition of economic development: to improve the quality of life for residents.

Too often, I think this gets conflated with a strategy of economic development, namely helping local entrepreneurs start new businesses to create new and good-paying jobs. Better paying jobs are certainly one way to improve the quality of life - it gives people more options and opportunities - but it isn’t the only way.

My definition also includes innovations that make a higher quality of life more accessible.

Put another way, if you think about a person’s income statement, you can increase revenue or decrease expenses to put more money in their pockets. The best case is doing both. Increasing the amount of discretionary money increases what they are free to do - both now and in the future.

What does this look like practically?

It means expanding the purview of local capital from only investing in startups that come from this place to also investing in startups that are for this place.

Instead of only advertising,

‘We are investing $500k checks into companies that headquarter here.’

you’d also advertise things like,

‘We are investing $500k checks into companies that can reduce the cost of housing, solve our lead paint problem, increase access to transportation for employment, or solve the prenatal care gap.’

Cities can just as easily request what startups solve as they can where startups locate. There is value in startups building products and services that improve housing, transportation, education, job access, financial health, and a myriad of other things. That is true even if that company is not physically located in your city. Sometimes innovations that come from the outside can do things that are a struggle locally. Local capital should not arbitrarily shut those out from its investing universe because of the mailing address of the company headquarters. Sure, we may not get the job creation benefits or the tax revenue, but those aren’t the end-all, be-all.

The goal is improving quality of life. Expanding from a strictly “from” capital strategy to include a “for” strategy can increase our ability to do so.

What are the advantages of including a “for this place” investment strategy?

Capital as Advocacy

Investing early in solutions allows your community to shape what a company ultimately builds. Companies are not predetermined machines, they are path dependent and if customers in your city are early adopters, that will show up in what is built and prioritized. This strategy turns local problems into opportunities. If local capital backs a compelling solution to a local problem that also happens to affect other communities, your community can actually see returns for having catalyzed it.

Independent of Local Deal Flow

Many cities are trying to figure out their innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystems. They are nascent, small, and still looking for their identity. This can make traditional place-based investing hard at times because the deal flow is just not there yet. Adding a “for” strategy is independent of ecosystem maturity - you can start regardless of the robustness of current “from” supply.

Expands the Investing Universe

Piggybacking on the last point, the number of companies that may be building products and services that can improve your community is most likely much larger than those coming from your community. This wider net means more opportunities to see interesting, high-quality companies that can both serve your community and deliver returns.

A Bigger Tent

This strategy allows you to get more people involved. You’re not only engaging people in the entrepreneurship community, you’re also bringing together people who are problem experts and partners who understand your community's challenges and may spend little or no time in the traditional entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Local Networks are Powerful

Local networks are valuable to both the founders and the investors. Founders get access to potential customers and partners at an early-stage. Investors get access to local expertise that can improve their due diligence and investment decisions. And if an investment and pilots do happen, both win.

“Traveling Salesman” & Intercity Connectivity Benefits

The connectivity of small cities is powerful for new ideas, businesses, and innovations. When you become an investor in an external company that serves your community, you’ve added a new node for your city. New connections are made, new ideas are shared, and the dynamism of your city increases.

Examples in the Wild

Examples abound for the “from” model of investing - city-specific funds and accelerators (see Buffalo, Birmingham), state-backed funds (e.g., Elevate Ventures in Indiana), and national firms with geographic theses (Rise of the Rest). Some of these only invest in companies from their communities, others also invest in companies that want to move to their communities. Most are still young experiments - a decade old at the most.

The hard part about the firms with hard requirements around where the company locates is that it becomes a zero-sum game, turning the old smokestack chasing game into a techstack chasing one.

Layering on a “for” strategy lets you play a positive-sum game. Startups aspire to serve customers in more than one city, and if you’re an investor as well as a customer, you’re fully aligned with that. It allows cities to collaborate with each other, rather than compete in a race to the bottom on incentives, funding, and amenities. And in an age where it’s hard to even define what a “headquarters” means for many companies, it takes some pressure off.

There are bright spots of organizations that are leaning into the idea of investing for a place. Blue Ridge Labs in NYC explicitly goes after the earliest stages of this, running what looks a lot like a venture studio, focused on solving problems for New Yorkers. The Ohio Impact Fund is putting from and for together, investing in Ohio-based companies that make Ohio a better place to live. The Urban Innovation Fund is investing to improve urban cities writ large.

There is a lot of room for more “for” strategies. They don’t all have to be the same. They don’t have to preclude or replace a “from” strategy. They are just another tool to pursue the ultimate goal.

All In

We have the luxury of sitting down and writing long-form newsletter posts about these distinctions. At the extremes, in places like Léogâne and for people like Paul and his brother, this is a silly nuance to name. Of course you’d invest in both “for” and “from”. There is no time for these debates - there are problems to be solved, jobs to be created, communities to build.

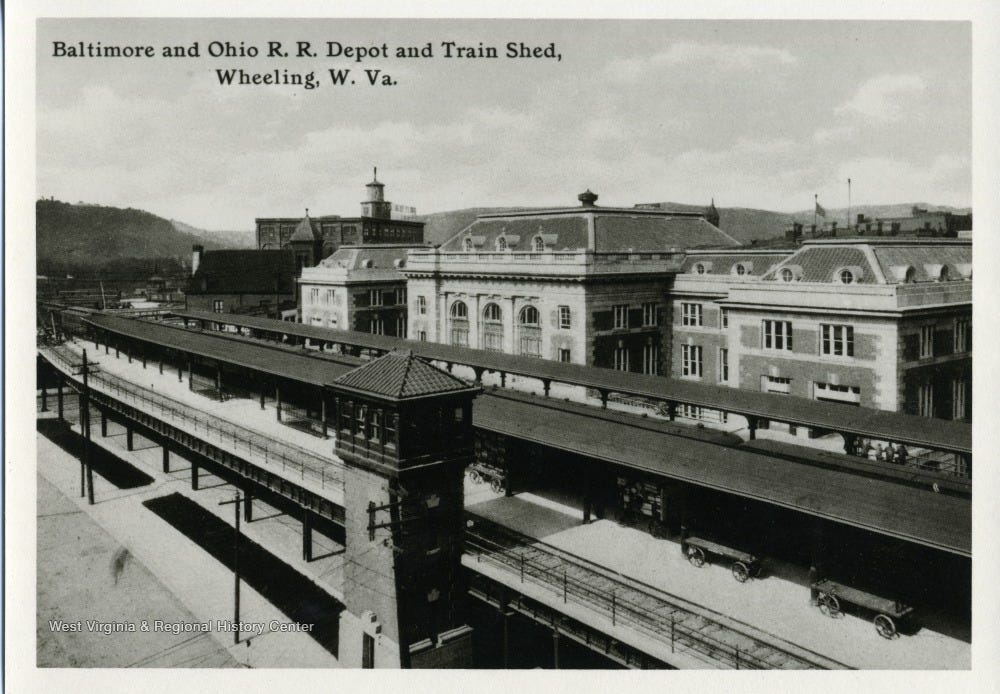

In my research for the new podcast project I’m working on, I came across this quote about Wheeling, WV back in the early 19th century:

The city fathers and the mercantile elite were the same people, and enterprise was their game. When it was necessary to subscribe capital to some new industrial venture, they complied eagerly. Similarly, when huge bonds had to be posted to bring in the Baltimore & Ohio (Railway), or even to guarantee P.T. Barnum’s gate on a concert by Jenny Lind (“The Swedish Nightingale”), they were ready with their purses. They were, in the slang of a later day, go-getters.

There are less boundaries between local economic development and local investing than we artificially create. Often they have a simple shared goal - improving livelihoods. Before we had frameworks, models, and entire institutions dedicated to the practice, we just had problems and problem solvers. Leaders like Paul and his brother.

We don’t have to wait for things to improve in our cities. Sometimes this means building things ourselves. Other times, it means scouring the world for innovations that can make our cities better. There will be some convincing, negotiating, and things that don’t work out. But there is a world of possibility in a small mindset shift of considering ourselves not just from a place - but also for a place.

» Check out more of Dustin’s writings at The Small City Segment

Innovative Finance Quick Hits