How to make lemonade

GPs, before you throw out those lemons in your portfolio…

GPs, before you throw out those lemons in your portfolio…

Venture Math Refresher: ⅓ , ⅓ , ⅓

Roughly one-third of venture investments fail. The middle third collectively get the fund to a 1x. The top third of investments make or break a venture fund.

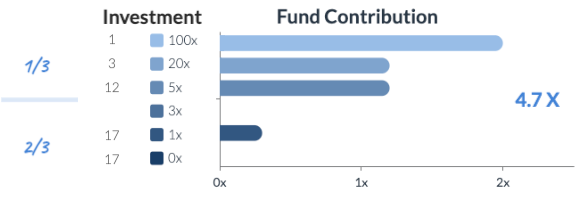

A high-performing 50-company VC portfolio might look like this:

This creates an obvious incentive for fund managers to focus exclusively on the upper third, investing all their time and follow-on capital there. If those returns are realized, the reward is a stellar MOIC of 4.7x (and IRR likely well into the top quartile).

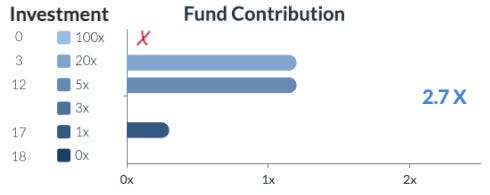

And, if that one outlier flames out?

The overall MOIC drops to 2.7x. That one deal made up almost 43% of the fund’s return.

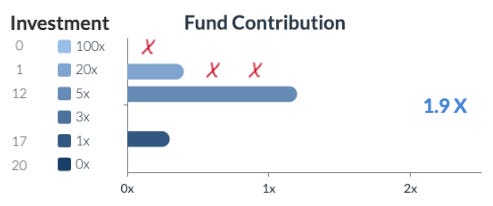

Add two more misses of medium exits, and MOIC drops to 1.9x.

Time spent with the "tweeners" remaining is often simply to get the capital back. A return that is meaningful to the fund overall isn't likely, or, as the math shows, important.

That is more or less how venture capital funds returns work.

However, the variance of returns for the asset class is incredibly wide.

Top quartile = 17 to 79% IRR

Median ~ 8% IRR

Bottom quartile = 0 to -22% IRR

Why?

The rule of thirds is only in hindsight.

At the time of investment, every GP believes they have found the top of the top third – the outlier fundmaker. And they repeat that conviction with every check they write, well aware that they’re almost always wrong.

Statistically, it takes 100+ investments to confidently find the outlier that makes or breaks a fund. A fund of 40-50 investments is statistically unlikely to find the investment for the fund to be successful. Maybe you can bend that math with networks, industry focus, specific criteria, etc., but it is still incredibly difficult to pick winners.

The key to success may simply be a matter of right place, right time - aka luck.

So what do GPs do when they realize a company isn’t on track to land in the top third?

The best GPs still work with the middle third of the portfolio, but most GPs I’ve spoken to spend very little time there.

And that is exactly where venture investors overlook a lot of return potential.

Deal structure can create the incentive to spend time with the middle.

Like middle children, the middle-third-performing investments tend to get less attention than the upper third because they are highly unlikely to become a “grand slam.”

What would the portfolio look like if the lower two thirds could could move from generating an average of 0-1x to creating a 2-4x return?

And how would that work outside of a fire sale or secondaries? These are common but not preferred venture exit strategies for the lower thirds.

And could this be done without ruling out the possibility of a large return outlier?

We do this with a structured exit.

As a company starts to succeed financially, they buy us out at a preset multiple of our original investment (read more about this redeemable equity structure here).

So how does this change the math?

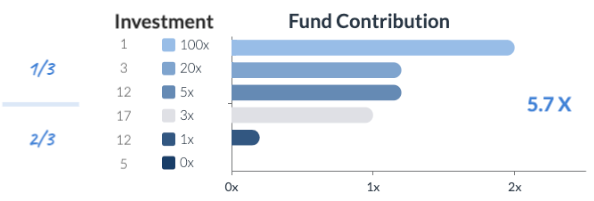

Start with the same mix of 50 portfolio companies.

As the bottom two-thirds start to reveal they aren’t on track for an outlier exit, we can shift to sustainable growth mode. Through structured exits alone, where a typical VC fund sees 0-1x for the fund, we can transform to find 1-3x.

Say we conservatively find an aggregate 1x multiple to the overall fund return through these structured exits:

A 5.7x would put you into rarified air as a GP.

This doesn't eliminate the requirement to find outliers, but it changes the magnitude those outliers need to be.

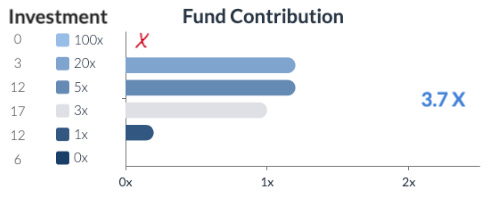

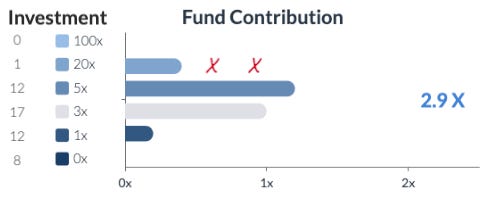

And if we miss the outlier that dominates the fund return?

It still hurts, but generates a 3.7x - still a solid performing fund.

And with two more misses of medium exits, returns are down to 2.9x, still ahead of the median for venture capital.

Moreover, whereas exits take 5-7 years on average, liquidity from structured exits typically occurs much earlier. This can add as much as 4-5% to the overall funds IRR.

Don’t let your lemons go bad

One of our portfolio companies hit some real headwinds during the pandemic and switched into “staying alive” mode. This temporarily took them out of the “upside” group and into what VCs call “zombieland.”

As opposed to “salvaging” or “firesaling”, we both still saw solid return potential. This also made digging in with the founders that much more enjoyable.

Now maintaining a slower growth rate, they continued to redeem some of our equity back, returning about half the initial investment. Having stepped off the venture treadmill, we also helped them access other parts of the capital stack, including some debt.

Come early 2022, they found a more offensive posture again and raised a venture round at a $12.5M pre-money (and a nice 5x markup).

In collaboration with the company, we converted part of our equity right and kept a portion to continue to be redeemed through the structured exit (which was revenue share in our case).

This gave us line-of-sight to a multiple and the potential for additional upside on the equity side.

In turbulent times (required reading: Minsky moments), this hedge is a helpful tool. Given the state of venture rounds and exits this past year, the multiple we structured in will serve us well. If they end up becoming that outlier exit, we can still participate through our unredeemed equity too.

And crucially, the founder still has ample opportunity for a life-changing outcome.

Suddenly, the extra attention on the middle of a portfolio is rational.

Let’s make some lemonade.